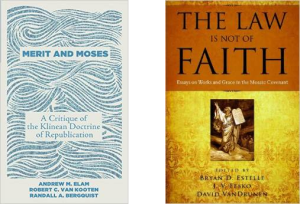

Over at Old Life, D.G. Hart has written this piece on the recently published book Merit and Moses by Andrew Elam, Robert Van Kooten, and Randall Bergquist (Wipf & Stock, 2014). As the subtitle indicates, the book is a critique of a relatively obscure and ambiguous doctrine known as “republication.” This doctrine has been around in some form or another since the beginning of Reformed theology, but its most recent permutation is associated with Meredith G. Kline, deceased professor of Old Testament at Westminster Theological Seminary in Philadelphia. Kline was the father of one of two camps at WTS that divided after the time of Geerhardus Vos—the other camp following John Murray, professor of Systematic Theology. The differences between these two camps centered on questions concerning the nature of covenant theology, law, and grace.

These days, the most ardent defenders of Kline and republication can be found at Westminster Seminary California. A few years back, the faculty of WSCal published the book The Law Is Not of Faith: Essays on Law and Grace in the Mosaic Covenant (P&R, 2009), the main thesis of which is that the Mosaic Covenant is “in some sense” a republication of the Covenant of Works. That turns out to be a rather confusing qualifier: in exactly what sense is it a republication of the Covenant of Works? There are at least three ways (and probably more) in which the Mosaic Covenant has been said to “republish” God’s original covenant with Adam:

- The Mosaic Covenant republishes the same moral law that was revealed in the Covenant of Works.

- The Mosaic Covenant republishes the “works principle” of the Covenant of Works in the specific and typological sense that Israel’s obedience merited the reward of possession of the Promised Land, just as Adam’s obedience would have merited the reward of eternal life. But Israel’s imperfect obedience also foreshadowed the perfect obedience of the True Israelite (Jesus), just as the temporal reward of Canaan foreshadowed the eternal reward of the New Heavens and New Earth.

- The Mosaic Covenant republishes the “works principle” of the Covenant of Works in the general sense that God rewards perfect obedience with eternal life.

Interpretation (1) above is relatively uncontroversial; the consensus of Reformed theologians is that Adam and all his posterity are—and always have been—subject to the same unchanging moral law of God. But taken in this sense, the idea of “republication” becomes redundant; every covenant of the Bible republishes the same moral law first revealed in the Covenant of Works. Sinai is no different.

Interpretation (2) is unique to Kline and his followers. It also happens to be the view of republication that has attracted the strongest criticisms. Most Reformed theologians are leery of admitting any kind of merit into the Mosaic Covenant—even if it is of a merely typological kind—since it would undermine the sufficiency of God’s grace. Indeed, how could an Israelite not slip into a legalistic mentality, knowing that their own personal obedience was earning them a place in the Promised Land? A rebuttal to this understanding of republication can be found in Scott Sanborn’s article “Did Paul Really Teach Republication as ‘Defined’ by VanDrunen? Part 3” in Kerux 27.3 (available online here), and in Cornelis Venema’s article “The Mosaic Covenant: A ‘Republication’ of the Covenant of Works?” in Mid-America Journal of Theology 21 (available online here).

Interpretation (3) is admittedly more widespread in the Reformed tradition (Calvin himself affirmed it), although it has been increasingly challenged—or at least nuanced—in recent years. On this reading, the Mosaic Covenant presents Israel with a hypothetical offer of eternal life through works-righteousness: if they could obey God’s law perfectly, they could earn God’s favor, but since they can’t, the law only mocks them with its impossible demands. [1] Presumably, this was the same arrangement that Adam had with God before the fall, with the crucial difference that Adam was originally capable of meeting the condition of perfect obedience. Taken in this sense, the law is seen as preparatory for the grace of the gospel. It enslaves, crushes, and ultimately kills sinners, forcing them to flee to the freedom found only in the perfect obedience of Christ.

Now there are certainly elements of truth in this reading (after all, freedom is only found in Christ). But it runs into difficulties in incorporating all of the biblical data into a coherent picture. For one, how does it square with Moses’s own words in Deut. 30:11-14 that the law isn’t too hard for Israelites to obey? Or how does it square with the words of the psalmist, who claims to have received life through God’s law (Ps. 119:93)? [2] And of course, we can’t forget that in the New Testament, James calls it a “law of liberty,” not a law of slavery (Jas. 1:25). The basic error of interpretation (3) seems to stem from viewing the law’s promise of “life” in strictly forensic terms. Should such “life” be regarded as entrance into God’s favor (i.e., justification), or rather as the fullness of blessing for those already in God’s favor? If we take the latter view (as I think we should), then republication again becomes redundant, for this promise of life/blessing is found in every covenant of Scripture.

This, in a nutshell, is one of the key dividing lines between followers of Murray and those of Kline. In my humble opinion, the Murrayans are closer to the truth here. Nevertheless, I do wonder if perhaps the best way forward is to go backward. That is, it may be the case that the Murray/Kline debate has only muddied the waters, and we will only find clarity by returning to even earlier Reformed writers—ones like Robert Rollock, Thomas Goodwin, or Patrick Fairbairn, for example. To be sure, nobody’s theology is perfect, and that’s why what we need most of all is a willingness to listen—even to those on the other side of the fence, even when they criticize our most cherished theological heroes. On that point, I think that Hart is spot on.

Notes

1. For a pithy critique of the idea of “hypothetical works-righteousness,” see Walt Kaiser, “The Law As God’s Gracious Guidance for the Promotion of Holiness,” in Five Views on Law and Gospel, ed. Stanley Gundry (Zondervan, 1996), 190-92.

2. Some interpreters have suggested that this and the other psalms of the “righteous man” must be referring exclusively to Christ, the only man capable of finding life through the law. But the problem with this reading—apart from the fact that no NT author uses these psalms in such a way—is that these very same psalmists also confess their sin and guilt before God (Ps. 41:4; 119:176), something that Christ himself never could have done.

July 19, 2014

July 19, 2014

How could Adam have been subject to the moral law? Laying aside the absence of such a notion in Gen 1-3 we may ask… could Adam commit adultery? Did he know what adultery was? How could he covet his neighbour’s wife? Would God suggest to him through laws what he had not conceived – graven images? The law was given to fallen people with the knowledge of good and evil. Moreover the moral law was more than the Ten Commandments. In fact, ultimately, if commanded by God the whole law is moral.

I’m not sure what you mean by every covenant republishes the moral law. Moving from systematics to biblical theology (a much safer place in my view) where is the moral law in the Abrahamic covenant. Abraham is justified by faith. There was no mention of a Sinai type law to either Adam or Abraham. I accept that Abraham would have the law in some sense written on his heart (Genesis often speaks as if Abraham was obeying the precepts of the law) but the covenant was not a law covenant. Nor was the Davidic covenant. The New covenant supposes the law written on the heart but those under that covenant are expressly freed from the mosaic covenant; they serve in the new way of the Spirit and not in the old way of the written code. Paul rejects circumcision and dietary laws not as a section of the law he no longer thinks applicable but as part of a whole covenant that is finished. I should add it was a covenant only Israel was under (Romans 2).

By the law is the knowledge of sin. Law exposes, excites and exaggerates and makes it sinful. Is there much evidence of ‘law’ preaching in the NT? A little I think. Certainly sin needs to be exposed. However, Im not sure this is how we should understand the redemptive – historical nature of the law. It was an interim measure until Christ came. It was a disciplinarian/pedagogue that taught and controlled children until Christ came. The law is not of faith, that is it s a covenant of works; faith came redemptive-historically with Christ (though of course faith was always present even if the covenant demanded works not faith).

Broadly I find myself in agreement with the WestCal on this issue. Deut 30 is an interesting text. It comes in the context of a renewed Israel. God has circumcised their hearts. To such a people the law is near. It is indeed ‘in your hearts’. Paul against a background of an Israel seeking to attain righteousness by law rather than faith lifts Deut 30 and applies it to the gospel. I suggest this is more than an application and is an interpretation.

Jas 1:25… the perfect law of liberty probably is looking at the whole revealed ‘word’. They are to be doers of the word. This would include the gospel word by which they were born again.

Psalm 119 has always puzzled me a bit. It seems to defy Romans 7. Again the first thing to be said is the law in which he delights includes but is much wider than the mosaic law. Secondly it is the response of a renewed heart. Indeed it seems to be one with new covenant blessings – the law is written on his heart.

More reflections Kyle… all a bit piecemeal. Hope they stimulate reflection.