This blog post is probably at least twenty years too late, if not much more so. Christians in America lost the gay marriage debate long before the Supreme Court’s Obergefell v. Hodges decision. When the best response we can give to why the government shouldn’t legally recognize same-sex marriage is “because the Bible says it’s a sin,” then we probably aren’t going to win very many hearers—especially among those outside the church who don’t care much what the Bible has to say.

But I’m not writing this primarily for those outside the church. I’m writing this primarily for the next generation within the church. Even inside the church, support for the traditional view of marriage is waning. According to Pew research from 2017, American evangelical Protestants of my own generation (Millennials born between 1981 and 1996) are far more likely to support legalized same-sex marriage than their elders—45% support vs. 23% support. Among younger Millennial evangelicals, support for gay marriage actually outstrips opposition to it (47% vs. 46%). And in my experience as a Christian high school teacher, I have strong reason to think that such support is much, much higher if we include the younger Generation Z—many of whom are already starting to have difficulty remembering what our society was like before Obergefell.

This is a problem. Unsurprisingly, there is a direct correlation between church attendance and support for LGBT+ rights—which tells us that as younger evangelicals buy more and more into the tenets of the Sexual Revolution, the demands of the gospel will make less and less sense to them. They might continue to call themselves Christian, but their lives won’t show it. So if we hope to keep the next generation of the church within the church, then we need to be able to communicate the traditional view of marriage—as an institution where one man and one woman are joined together in a sexual union intended to be exclusive and permanent—in a way that makes sense to them.

In what follows, I’m going to evaluate four basic options when it comes to Christians’ stance on legalized gay marriage. In doing so, I’m going to assume agreement with the Bible’s teaching that homosexual behavior is in fact sinful. If you have any doubts about that assumption, then I’d encourage you to first read Kevin DeYoung’s What Does the Bible Really Teach About Homosexuality? before continuing further.

For the sake of simplicity, I’m deliberately painting with a broad brush here, so there might be possible variations within each of these four options. However, I think these options pretty well cover all the logical possibilities for Christians. So here goes:

1. The accommodationist response: “Gay marriage is wrong biblically and morally, but it should still be tolerated legally.”

This is probably the majority view among Millennial and Generation Z evangelicals by a substantial margin. I call it the “accommodationist” view because it seeks to harmonize biblical principles of morality with secular principles of legal toleration. There are several arguments I often hear in support of this view:

- “Christians don’t have the right to impose their religion on others.”

- “Gay marriage doesn’t harm anyone.”

- “Outlawing gay marriage will only drive gay people away from the gospel.”

- “Christians will be seen as bigots if we don’t tolerate gay marriage.”

In my humble opinion, all of these arguments are wrongheaded, making the accommodationist response the worst possible option for Christians. To begin with, the traditional view of marriage is not a uniquely Christian teaching. Societies around the world since the beginning of history have recognized marriage as exclusively between man and woman. In fact, even societies that celebrated homoerotic relationships, like ancient Greece, had no concept of legalized gay marriage. So for those who think that opposition to gay marriage can only be religiously motivated, I would ask, how is it that so many societies around the globe—even those that never even heard the name of Jesus—could be in such widespread agreement? Why is it that the idea of gay marriage emerged only in the West in the past couple decades?

The accommodationist view is also mistaken to suppose that nobody is harmed by gay marriage. Gay marriage is profoundly harmful for society, and especially for children. Unlike the traditional view of marriage, which is centered on the needs of children, gay marriage is centered on the wants of adults. For most gay marriage proponents, marriage is nothing more than a private arrangement based on the spouses’ subjective feelings of emotional fulfillment. If either spouse ceases to feel fulfilled staying in the marriage, there’s nothing to stop them from getting a divorce (after all, when is the last time you heard a gay marriage proponent speak out against gay divorce?). Likewise, if either spouse ceases to feel sexually fulfilled inside the marriage, there’s nothing to stop them from seeking sexual partners outside the marriage. As a result, the traditional marital norms of permanence and exclusivity are undermined by gay marriage.

This is disastrous for the well-being of children. As study after study has shown, children fare better in every way (emotionally, educationally, financially, legally, etc.) when they are raised by the two parents who naturally produced them. Gay marriage redefines marriage in such a way as to make this ideal family environment harder to recognize and to realize.

Likewise, accommodationists are mistaken to think that banning gay marriage would drive gay people further away from the gospel. Do we use this logic for any other vice? Should we be concerned that outlawing prostitution will drive prostitutes away from the gospel? Or that outlawing recreational drug use will drive heroin addicts away from the gospel? Do we really think that prostitutes and addicts would start coming to Christ in larger numbers if we just legalized their vices? If anything, it’s legalizing gay marriage that drives gay people further away from the gospel. By redefining the legal norms for marriage, social norms will inevitably follow. And as the divide between social norms and biblical norms increases, the biblical norms will make less and less sense. As Christians in past centuries knew well, the laws and customs of a society can serve as a kind of praeparatio evangelica or “pre-evangelism,” making the gospel more plausible to the citizens within that society. On the other hand, laws and customs that are directly opposed to the gospel will serve to make the gospel seem less plausible.

Lastly, accommodationists are mistaken to think that, just because they tolerate legalized gay marriage, they will not be considered bigots. If they confess the Bible’s teaching on marriage and sexuality at all—even if only on a “moral” level—proponents of the Sexual Revolution will still denounce them as intolerant and hateful. The proper response to being called a “bigot” is not to compromise our message, but rather to press our critics on what they mean by the word “bigot.” By requiring them to define their terms, we can in some measure prevent them from using such terms as rhetorical bludgeons. Of course, that will only get us so far. The reality is that Bible-believing Christians are going to be called bigoted, no matter how graciously we communicate the Bible’s teachings. The gospel is inherently offensive to those who are perishing.

2. The libertarian response: “Get the government out of marriage entirely, and let it be a private institution.”

In my opinion, the libertarian response is a more reasonable option than the accommodationist response, although it still has its flaws. Those Christians who opt for this approach tend to come in two types: 1) ideological libertarians, who believe that the state doesn’t have a right to exist at all, and 2) more pragmatic libertarians, who acknowledge some legitimate sphere of authority for the state, but who believe that privatizing marriage is a realistic solution given our current circumstances. [Edit: as stated above, I’m being deliberately simplistic here. There are more nuanced shades of libertarianism than what I’m presenting, but I think my critiques here still stand.]

I’m not interested here in a full critique of ideological libertarianism. For now, I would just say that I think that such Christians are seriously misreading Romans 13:1-7. Paul wrote those words to Christians living under the reign of Emperor Nero, which sets the bar pretty low for legitimate governing authority. If Christians back then had to submit to Nero, then we certainly ought to submit to our governing authorities today. Of course, submission has its limits, and there are appropriate times for civil disobedience, but I won’t get into that question right now.

Here I’ll address the pragmatic libertarians who think that privatizing marriage might give Christians an easier way out of our current cultural predicament. To their credit, I would say that I see nothing wrong with their view in principle. As Christians, we recognize that marriage exists ontologically prior to the state. That is, before Adam and Eve fell in the Garden, they had marriage but no civil authorities. Therefore, marriage does not depend on the state for its existence. However, given our current political circumstances, I don’t think that privatizing marriage will have the effect that libertarians intend. In fact, it would probably make matters even worse.

The first problem is that a healthy marriage culture depends in part on healthy marriage laws. As mentioned above, the legal norms of a nation tend to influence its social norms. In the minds of many people, what’s legal is normal, and what’s normal is good. By removing all marriage laws, citizens will have a harder time recognizing marriage as a distinct social good. And when marriage is harder to recognize, it’s harder to achieve the goods that marriage provides, such as stability and commitment. Again, the biggest victims of the erosion of a healthy marriage culture will be children.

The next problem is that state involvement in families is inevitable, especially when marriages break down and someone needs to pick up the pieces. Government agencies and bureaucracies will have to step in to deal with the collateral damage resulting from divorces, including issues of property, custody, alimony, welfare, and incarceration (children in poor, single-parent households are much more likely to commit crimes). As the family gets weaker, the state gets bigger. So if you care about small government, then you should care about the government caring about healthy marriages. That means having appropriate laws in place to protect this vital yet fragile institution.

3. The theonomist response: “Outlaw gay marriage because it goes against Scripture. Society should conform to a biblical worldview.”

There are a number of terms we could use to describe this approach. It could also be called the “presuppositional” or “biblicist” approach, since it deliberately presupposes the truth of Scripture in making its case. I call it the “theonomist” response after the Christian Reconstructionist movement of the 20th century, which included such figures as R.J. Rushdoony and Greg Bahnsen. What made their approach unique was the belief that Old Testament civil laws—including penalties against such crimes as adultery and blasphemy—be applied to modern society. Of course, theonomists weren’t the only ones to appeal to Scripture in making the case against legalized gay marriage. This was also the favored approach among the Religious Right in the 1980s and 1990s. The advantage of this approach is that it is quite easy to point to passages of Scripture to show not only that marriage should be between man and woman, but also why. Scripture teaches that marriage is supposed to reflect the relationship between Christ and the church (Eph. 5:32), and the roles in this relationship are most certainly not interchangeable.

However, there are a few problems with the theonomist approach. To begin with, this approach simply won’t work within our current system of constitutional government. The accommodationist objection of “imposing one’s religion” actually has some merit here. The First Amendment does forbid any laws that prohibit the “free exercise” of religion, and an argument based purely on special revelation will likely be seen as an infringement on others’ religious liberty.

A related problem with this approach is that, since it appeals directly to Christian Scripture, it probably won’t have much persuasive force among those who don’t share biblical presuppositions. Now it is true that Christians have a deeper understanding of the meaning of marriage because of their belief in Scripture. But that doesn’t mean that unbelievers have no understanding of the meaning of marriage. Special revelation is not the only source of truth about marriage. So from a rhetorical standpoint, it would be wise for Christians to find points of contact with unbelievers using general revelation to make persuasive arguments for the traditional view of marriage.

One final critique of the theonomist view [edit: with the caveat that not all theonomists say this, but for the sake of simplicity, I’m making generalizations]: although they are right to highlight the purpose of marriage as reflecting Christ and the church, that is not the only purpose of marriage. In fact, I would argue that it is not even the primary purpose of marriage. As we read the biblical grand narrative of Creation-Fall-Redemption-Restoration, we find marriage all the way back at the beginning. It was instituted by God himself before Adam and Eve sinned (Gen. 2:18-24). Back then, before sin entered the world, there was no need for Christ’s Atonement or the institutional church. Therefore, Adam and Eve could not have known that marriage is supposed to reflect Christ and the church. So what could Adam and Eve have known that their marriage was for? The answer points us back to Genesis 1:28: “Be fruitful and multiply.” This also brings us to the fourth Christian response to gay marriage.

4. The natural law response: “Outlaw gay marriage because it undermines the objectively recognizable social goods achieved by real marriage.”

While some might say this argument sounds Roman Catholic, I have argued elsewhere that the natural law tradition has roots in early Protestantism as well. American evangelicals largely forgot this tradition in the 20th century, but I believe it would be valuable to us in the gay marriage debate today. If we are going to argue that the state should recognize some forms of marriage and not others, then we should do so on grounds that are rationally accessible to all people, and not just on grounds knowable only to Christians. That’s where natural law helps us. Natural law is the objective moral order based upon humanity’s nature and purpose, which is knowable through human reasoning and intuition alone, apart from the Bible. So we should ask, what can we know about marriage through human reasoning and intuition alone, apart from the Bible?

Some would rightly point to the natural complementarity between man and woman. Such complementarity means that men and women are fit for each other—anatomically, emotionally, and socially. By contrast, homosexual relationships cause physical damage to the body, and they tend to amplify the respective weaknesses of each sex. For example, traditional conjugal marriage generally has the effect of settling men down, making them more stable both in their careers and in their sex lives. But in gay marriages, this is not the case, since gay husbands are promiscuous at astronomically high rates. Likewise, traditional conjugal marriage provides greater emotional and financial security for women, but lesbians divorce at higher rates than anyone else.

However, there is a problem with using this as an argument against legalized gay marriage. In appealing to statistical regularities, critics can always point to the outliers: what about the gay husbands who are faithful to each other for a lifetime? What about the lesbian wives who never divorce? What’s more, what about all of the straight marriages where the husband cheats or the wife divorces? Why should the law punish everyone for the faults of only some (or even most)? Further, the argument from male/female complementarity appeals primarily to the harm that gay marriage causes to the spouses. But when we are talking public policy, arguments that demonstrate social harm are generally more compelling than arguments that only demonstrate harm to oneself. Therefore, I would not appeal to the complementarity of man and woman (valid though it may be) as the primary reason for not legalizing gay marriage.

One reason stands out above all others for why the state should take an interest in protecting the traditional institution of marriage: babies. It’s a biological fact that it takes a man and a woman to make a baby. This is nature’s design. Of course, there are technologies today that could attempt to subvert that natural design—such as cloning and IVF. But human artifice cannot undo the reality that every child needs—and has a right to—a mom and a dad. The welfare of children is the primary reason why societies around the globe and throughout history have recognized marriage as between man and woman. As marriage advocate Maggie Gallagher once said, “Sex makes babies, society needs babies, and children need a mother and a father.” It’s as simple as that.

Just consider how marriage’s orientation toward procreation makes sense of all of the other norms of marriage that most of us take for granted. The openness to procreation explains why marriage must be between only two people, why it must be a sexual union, why it must be permanent, why the spouses must be biologically unrelated, and why marriage needs legal protections.

On the other hand, none of these norms make any sense if marriage is ordered fundamentally toward the emotional fulfillment of the spouses rather than toward the needs of any children that the relationship produces.

Now don’t think that I’m making a slippery-slope argument here. I’m not saying that allowing gay marriage will inevitably lead to these other types of relationships being called marriage too. What I am saying is that marriage loses its definitional coherence if its foundation is only in spousal emotional fulfillment. Gay marriage proponents can say that marriage should be only between two people, be permanent, etc., but what they cannot do is give a coherent reason why that should be so.

Now of course, there are several objections to the claim that marriage should be ordered toward procreation. Even many evangelical Protestants might balk at such a claim. Some might ask such questions as, don’t infertile straight couples have a right to marry too? Would this mean that it’s wrong for straight married couples to intentionally choose childlessness? Doesn’t the fact that gay couples can adopt mean that they should have the right to marry too? To these questions, I would answer yes, yes, and no. Let me explain.

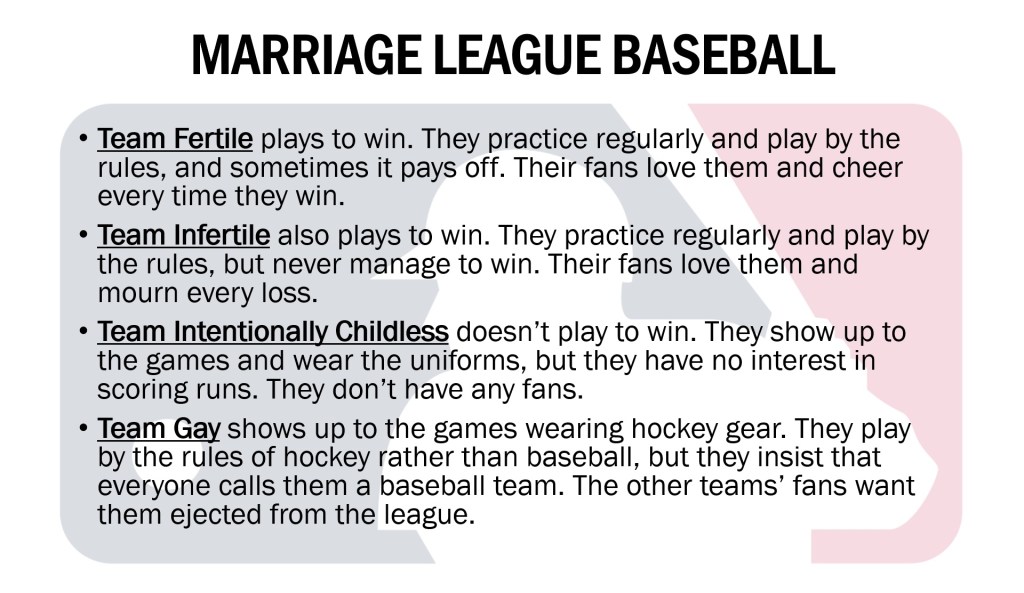

To begin with the infertile straight couple and intentionally childless straight couple objections, allow me to use this analogy from baseball:

As you can see here, whether a straight married couple is fertile or infertile, they are still “playing by the rules” of marriage, even if the marriage does not achieve its goal in procreation. Still, the fact that an infertile couple is unable to have children is a real loss for the couple, even though they are still able to achieve other goods of marriage, such as companionship and emotional support. But the important point is that these other goods shouldn’t run contrary to the structure of marriage itself—a structure that is defined by marriage’s orientation toward procreation. In the same way, a baseball team that never wins might still achieve other goods, such as sportsmanship and teamwork. And yet while other sports might also be able to achieve the goods of sportsmanship and teamwork, those other sports are not baseball.

The harder objection for many evangelicals is the question of intentional childlessness in marriage. Honestly, I think that the normalization of intentionally childless heterosexual marriages, made possible by the widespread use of contraception, has probably done more damage to the Christian view of marriage than even the LGBT+ movement. I know that’s a bold and perhaps controversial claim; however, the sinfulness of intentional childlessness in marriage was in fact the consensus view of Christians throughout most of church history. That consensus ended only in 1930, when the Anglican Communion held its decennial Lambeth Conference, becoming the first church body in history to formally permit contraception. Since that time, birth control has become more and more normalized among evangelicals, especially with the advent of the Pill in 1960. Birth control made it possible to sever the mental link between sex and babies, thus rendering the concept of sterile marriages more socially plausible. Arguably more than anything else, this is what shifted our understanding of marriage from being an institution ordered toward procreation to being a private arrangement ordered toward romantic companionship. And once intentionally sterile marriages became plausible, gay marriage was the next logical step.

Now don’t misunderstand me. I’m not saying that contraception is always wrong. There may be cases where using contraception might be the wiser course of action for a married couple, especially in cases where the mother or potential child faces serious medical risks. But this should be the exception and not the rule, and it shouldn’t be done so as a matter of mere personal convenience. Rather, procreation should be considered the “default setting” for marriage.

To use another analogy, consider adoption. We can rightly say that, under ordinary circumstances, a child has a right to his or her biological mother and father. This is the “default setting” for kids. And yet there may be exceptional circumstances that override this default setting—such as extreme financial hardship, lack of family support, etc. In such cases, placing the child in adoption might be the best thing for them. On the other hand, if a married couple decided to place their kid in adoption simply for the sake of their own personal convenience, that would be considered morally reprehensible. Barring cases of extreme necessity, we should regard intentional childlessness in marriage in a similar light.

I know that this is a stricter view than many evangelicals take on contraception. But the fact is that most evangelicals don’t think that much about contraception at all. They just go along with the culture uncritically. For those skeptical of my natural arguments up to this point, here I’d like to offer a few biblical reasons why we should treat contraception as the exception, and treat procreation as the default setting for marriage:

- “Be fruitful and multiply” is a command, not an invitation (Gen. 1:28). While some might look at the global human population and say that we can check this command off our checklist, the fact is that only God, not man, has a right to say when we’ve completed our God-given task. Plus, looking at current global trends, it appears likely that underpopulation is going to be a bigger problem than overpopulation.

- Scripture calls children a blessing from the Lord (Psalm 127:3-5). If a married couple considers children to be more of a burden than a blessing, then the problem is their own affections, not biblical truth. C.S. Lewis, famous for his children’s stories, admitted (quite ironically) that he did not personally “enjoy the society of small children,” but he recognized that as a moral defect in himself (The Abolition of Man, ch. 1).

- God tells us that his purpose for marriage is “godly offspring” (Mal. 2:15). In ancient Israel, this purpose was subverted by husbands abandoning their wives for unbelieving Gentile women. Today, it is subverted by couples who prioritize career and leisure over children.

- Onan, the only biblical example of intentional childlessness in marriage, is condemned for it (Gen. 38:8-10). And Onan’s problem wasn’t merely that he was flouting cultural conventions. His actions were actually “evil in the sight of the Lord.”

- Paul calls homosexual relationships “unnatural” (Rom. 1:24-27). What makes them unnatural is the fact that they are inherently and structurally sterile. Contrast this with an infertile straight couple, which is only accidentally sterile. That is, their infertility is a lamentable result of the Fall, rather than being inherent in their God-given, created design. Let me put it this way: when a wife desires to bear a child but is unable to do so, that is tragic. On the other hand, the fact that I, as a man, am unable to bear a child is not tragic. That’s simply not what my body was designed to do.

Now perhaps some evangelical readers at this point are still unconvinced of the wrongness of intentional childlessness in marriage. Okay, well for the sake of argument, let’s suppose that it’s not wrong. Still, that doesn’t change the fact that the state only has an interest in marriage because marriages produce children. Given the fact that marriage must have a certain structure in order to produce and raise healthy children (who in turn become productive, virtuous citizens), the state has an interest in protecting that particular structure of marriage. Intentionally childless straight marriages, though missing out on the spirit of marriage, do not violate the structure of marriage. In the same way, a baseball team that doesn’t try to score runs is missing the spirit of the game, even if they aren’t technically breaking any of the rules.

Lastly, let me deal with the gay adoption objection. It’s true that gay couples can adopt children. But this doesn’t mean that they should. After all, anyone can adopt a child. Siblings can. Friends can. Total strangers can. But that doesn’t mean that all of these potential adoptive arrangements are in the best interest of the child. As stated above, we already know that children fare best when they are raised by both biological parents. This is the family environment that our marriage laws should favor, and it’s also the family environment that our adoption laws should mimic, when possible. Now I recognize that the needs of the adoption system might sometimes outstrip the availability of two-parent families and require placing kids in less than ideal family environments. However, redefining marriage itself will only create more of the brokenness that adoption is meant to repair.

Conclusion

That, in sum, is my case for protecting the traditional definition of marriage as between man and woman. Like I said at the beginning, I think that Christians have already lost this battle, culturally speaking. I don’t think any force of reason or argument is going to turn the tide against the Sexual Revolution now. I’ve become increasingly sympathetic to Rod Dreher’s Benedict Option, so at this point I think the best we can hope for, short of a divine miracle, is for the bottom to fall out and for society to experience firsthand all the harms caused by abandoning a healthy marriage culture. Things are going to get a lot worse before they get better. In the meantime, Christians need to focus on fostering a proper view of marriage among our own kids, so that the church’s next generation will be equipped to remain faithful to biblical teaching. And the best way to do that, I believe, is to show that the biblical view of marriage isn’t just a biblical view of marriage. It’s a natural view of marriage.

January 4, 2021

January 4, 2021

hi

Very thorough. Many thanks.