Note: I originally presented the following paper in January 2013 for the second annual meeting of the Theological Fellowship at Covenant Seminary in St. Louis, Missouri.

Introduction

One of the ongoing debates within the evangelical world centers on the question of infant baptism—that is, should we baptize professing believers only, or should we baptize both believers and their children? As both sides of the debate agree, there is no explicit command in Scripture for one practice or the other, so it is generally believed that the matter must be settled indirectly, by determining the role that baptism plays within broader theological frameworks. This morning I’m going to survey various attempts to situate baptism within the context of the New Covenant.

The New Covenant is a recurring theme in Scripture. In the OT, it’s mentioned explicitly only once, in Jeremiah 31. According to this passage, which is found in the context of Judah’s promised return from Babylonian exile, the Lord makes a “new covenant” with the houses of Israel and Judah. This covenant is unlike the old covenant that their forefathers had broken; it leads to the internalization of God’s law and to the full forgiveness of sin. We could also connect Jeremiah 31 with the restoration prophecies in Deuteronomy 30 and Ezekiel 36. While these prophecies do not explicitly refer to a New Covenant, they do share the underlying idea that the Lord himself will deal directly with the problem that had necessitated Israel’s punishment by exile in the first place. Since the problem was Israel’s heart, God would intervene to change their heart. In the NT, the phrase “new covenant” is found in several places, including Luke 22, 1 Corinthians 11, 2 Corinthians 3, and Hebrews 8, 9, 12. These passages variously tie the New Covenant to the Lord’s Supper, to a ministry of the Spirit rather than the letter, to Christ’s mediation and sacrificial death, and to better, eternal promises.

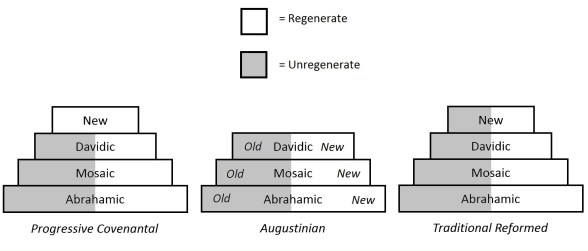

Now there is no passage of Scripture that explicitly ties the New Covenant either to the practice of baptism or to the children of believers. Connecting these three concepts must therefore be done inductively, based on inferences from the biblical text. In this paper, I will present and evaluate three different views on the relationship between the New Covenant, baptism, and believers’ children. These three views are not exhaustive of Christian views on baptism; rather, they represent three different perspectives from within the Calvinistic tradition. In the order that I am presenting them, they are the Progressive Covenantal view, the Augustinian view, and the Traditional Reformed view. The first view opposes infant baptism, while the second two support it. I will personally land between the Augustinian view and the Traditional Reformed view.

The Progressive Covenantal View

I begin with the Progressive Covenantal view. This position, which is gaining popularity among Reformed Baptists, is described primarily in two works—first, in Believers’ Baptism, edited by Thomas Schreiner and Shawn Wright (Nashville, TN: B&H, 2007), and most recently in Kingdom through Covenant, by Peter Gentry and Stephen Wellum (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2012). This second work seeks to take a middle ground between traditional Covenant Theology and dispensationalism; hence the name “Progressive Covenantalism.”

The essence of Progressive Covenantalism is that the New Covenant signifies a visible community consisting of spiritually regenerate believers only. Or in Wellum’s words, “All those within the ‘new covenant community’ are, by definition, people who presently have experienced regeneration of heart and the full forgiveness of sin.”[1] So unlike OT Israel, God’s people are no longer understood as a mixed entity of believers and unbelievers, but now every covenant member has a saving knowledge of the Lord. Progressive Covenantalists likewise understand the New Testament church as a heavenly and spiritual entity whose members are “in Christ,” but no spiritually unregenerate person can ever be united to Christ. Therefore, since baptism signifies union with Christ and New Covenant membership, Progressive Covenantalists argue that it should only be applied to those who show evidence of spiritual regeneration—that is, professing believers. You will notice then a significant implication of Progressive Covenantalism: it collapses the traditional distinction between the visible and invisible church—that is, the distinction between the visible community of God’s people and those within the community who are eternally elect.[2]

Now in my opinion, Progressive Covenantalism has three significant problems. First, we cannot baptize individuals on the basis of their status as eternally elect—a status which is unknowable to us. Rather, we could at best only baptize them on the basis of their profession of faith, which may or may not be genuine. This fact alone makes the visible/invisible church distinction inescapable.[3] Second, Jeremiah 32:39 declares that the New Covenant is for the good of both Israel and their children after them. The problem, as Jeremiah saw it, was not the presence of children in the covenant, but rather apostates. And third, Progressive Covenantalism cannot adequately account for the existence of covenant breakers within the church, such as we find in the NT warning and apostasy passages. Holding to the Calvinist doctrine of the Perseverance of the Saints, Progressive Covenantalists teach that it is impossible for those who are spiritually regenerate to lose their salvation. So if the New Covenant community is restricted to only those who are spiritually regenerate, then the New Covenant is by definition unbreakable. And yet Hebrews 6:4-5 says that there are individuals in the church who “have been enlightened, who have tasted the heavenly gift, and have shared in the Holy Spirit, and have tasted the goodness of the word of God and the powers of the age to come,” but who nevertheless fall away. Further, according to Hebrews 10:29, such an apostate has “profaned the blood of the covenant by which he was sanctified.” How do Progressive Covenantalists deal with such passages? They say that these verses only present a hypothetical scenario by which the author intends to spur his readers toward perseverance in their faith.[4] In other words, the threat is merely fictitious. But this sounds like special pleading to me. A natural reading of these warning passages strongly suggests that covenant members can and do fall away. I am convinced that another approach is needed.

The Augustinian View

This brings us to the second view, which may be called Augustinianism, after its most famous defender in church history, Saint Augustine of Hippo. In more recent years, it has been supported by J. Oliver Buswell, Robert Rayburn and our own Dr. Jack Collins. One of the most extensive treatments of this view is found in Joshua Moon’s recent publication, Jeremiah’s New Covenant (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2010).

To understand the Augustinian view, one must understand the difference between the objective administration of the covenant and the subjective appropriation of it. “Objective” refers to the various external structures, ceremonies, and sacraments that regulate the community of God’s people. “Subjective” refers to those individuals within the community who have embraced the covenant from the heart, clinging to its promises by faith—again, think visible and invisible church. Further, the objective side of the covenant may change progressively over time, as we see with the adding of circumcision, then the priesthood, then the monarchy, and so forth. But the subjective side remains the same throughout history; OT saints were saved in the same way that we are today. The Augustinian view teaches that the New Covenant refers to this subjective aspect of the covenant, not the objective aspect. This means that the New Covenant is not a redemptive-historical development of the Abrahamic, Mosaic, and Davidic covenants. Instead, one could say that Abraham, Moses, and David were themselves members of the New Covenant. And conversely, “old covenant” does not refer to a bygone era in redemptive history, but rather to individuals whose standing in the covenant is merely external. So similar to the Progressive Covenantal view, the Augustinian view also restricts the New Covenant to those who are spiritually regenerate. But the difference is that the Augustinian view still maintains a visible/invisible church distinction. The old and new covenants—faithless fakers and true believers—exist side-by-side within the covenant community throughout all ages, until the Eschaton.

Now with respect to baptism, Augustinians understand it to be an objective ordinance of the visible church. It may signify the spiritual realities of the New Covenant in a sacramental sense, but it does not automatically guarantee one’s status as a regenerate participant of the New Covenant. Therefore, Augustinians have no problem applying the rite of baptism to believers’ children.

Now in my opinion, the Augustinian view has a lot to commend itself, especially with respect to the OT data. First, it accounts for the close literary connection between Jeremiah’s New Covenant prophecy and Israel’s restoration from Babylonian exile. Second, it can take at face value the subjective aspects of Jeremiah’s New Covenant prophecy. And third, the Augustinian view can make sense of the fact that we see New Covenant realities expressed in the lives of certain pre-exilic saints. For example, in Jeremiah 31:33, the Lord prophesies, “I will put my law within them, and I will write it on their hearts.” But in Psalm 40:8, King David can also pray to the Lord, “Your law is within my heart.” Similarly, Deuteronomy 30:6 says of the returning Jewish exiles, “The LORD your God will circumcise your heart… so that you will love the LORD your God with all your heart and with all your soul.” But 2 Kings 23:25 says that King Josiah, who reigned before the exile, “turned to the LORD with all his heart and with all his soul.” So it seems hard to deny that subjective aspects of the New Covenant existed well before the Christian era. But the chief weakness of the Augustinian view, as I see it, is its difficulty in handling the NT data [see treatment below].

The Traditional Reformed View

This brings us to the third and final view, which I call the Traditional Reformed view. This position has been described in a number of works, including Richard Pratt’s essay, “Infant Baptism in the New Covenant,”[5] and Far as the Curse Is Found by our own Dr. Mike Williams (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R, 2005). According to the Traditional Reformed view, the New Covenant brings with it sweeping changes to the administration of the covenant. In fact, nearly all that distinguishes the NT church from OT Israel may be subsumed under the heading of the New Covenant. The arrival of the Messiah—New Covenant. The outpouring of the Spirit—New Covenant. The institution of baptism and the Lord’s Supper—New Covenant. However, for all the changes that the New Covenant brings, certain things remain the same. Just as the children of Israelites were included in the old covenant, so also the children of believers are included in the New Covenant. The New Covenant does not further restrict covenant membership, but rather expands it, so as now to include even the Gentiles. And since baptism is understood to signify membership in the New Covenant, it may also be applied to infant covenant members.

The NT evidence in support of the Traditional Reformed view seems to be pretty substantial. When Christ institutes the Lord’s Supper in Luke 22, he calls it the New Covenant in his blood. Now an Augustinian would interpret this statement sacramentally, in the sense that the Lord’s Supper is a physical sign of the spiritual reality of regeneration.[6] Now I agree that the Lord’s Supper is a sacrament, but is that all that Christ means in calling it the New Covenant? After all, in the OT, circumcision and the Passover were likewise sacraments, but would we say that they too constituted the New Covenant? In addition, Christ is called the mediator of the New Covenant in Hebrews 8, 9. But he did not assume his mediatorial role until after he had accomplished his work of atonement. Pre-incarnate Christ was not a covenant mediator. So either we have to say that the New Covenant existed unmediated prior to the Incarnation, or we acknowledge that in some sense the New Covenant was inaugurated by the mediation of Christ. The latter sounds more plausible to me.[7]

Conclusion

In conclusion, it might be helpful to frame this whole discussion in the context of the two Latin theological terms, ordo salutis and historia salutis. Ordo salutis, meaning “order of salvation,” refers to that “golden chain,” the personal experience of salvation that leads an individual from regeneration, to faith, to justification, to sanctification, to glorification. By contrast, historia salutis, meaning “history of salvation,” refers to God’s dealings with humanity in general throughout the course of world events. The three views we’ve examined this morning all relate the New Covenant to these two concepts in different ways. The Traditional Reformed view sees the New Covenant as a matter of historia salutis; the Augustinian view sees it as a matter of ordo salutis; and the Progressive Covenantalists want to have their cake and eat it too.

Now as I said previously, I personally think the truth lies somewhere between the Traditional Reformed view and the Augustinian view. It seems to me that Scripture does not use the term “New Covenant” univocally, with the same meaning in every passage. In some places, such as Jeremiah 31, the emphasis appears to be on the subjective side. But in other places, such as Hebrews 8, 9, the emphasis appears to be on the objective side. I do not think that these emphases are mutually exclusive; rather, they are complementary. The physical signs of the New Covenant administration are meant to point to the spiritual realities of a New Covenant relationship. Now you might ask me if I’m not trying to have my cake and eat it too. My response is yes, but not in the same way as Progressive Covenantalism. I do think that the New Covenant can be understood as both objective-visible-historia on the one hand, and as subjective-invisible-ordo on the other. But I also think that a distinction between these two categories needs to be maintained, at least until the church militant becomes the church triumphant. So I’m trying to integrate the strengths of each position. This in turn will have very practical implications, not least of which is addressing the question, should believers baptize their children? And in my personal opinion, the answer to that question is yes. If believers’ children are covenant members, and if baptism is for covenant members, then baptism is for believers’ children.

Appendix: Anticipated Objections from the OT to the Augustinian View

While I believe that the OT evidence generally favors an Augustinian reading, there are two potential objections from the OT that need to be addressed. First, I mentioned how Jeremiah’s New Covenant prophecy corresponds to the restoration prophecy in Ezekiel 36. In that passage, God promises to put his Spirit within his people, so that they will obey his commands. A similar idea is echoed in the prophecy of Joel 2, where God promises to pour out his Spirit on all flesh, so that men and women will prophesy and have visions. The apostle Peter quotes this very passage in Acts 2 on the day of Pentecost, inaugurating a new era in redemptive history. This would then tie the New Covenant to the Christian era. So this objection reasons from Jeremiah 31 to Ezekiel 36 to Joel 2 to Acts 2. The weakest link in this chain is the connection between Ezekiel 36 and Joel 2; they might refer to two different workings of the Spirit, the former being regeneration for the purpose of obedience, and the latter being outpouring for the purpose of supernatural gifts. This would then exclude Joel 2 from the category of New Covenant prophecy. This appears to be supported by Ezekiel 37, the vision of the Valley of Dry Bones. In v.14, the Lord says, “I will put my Spirit within you… and I will place you in your own land.” For Ezekiel, the Spirit’s activity is directly connected with the return from exile, not Pentecost.

The second possible objection is based on Jeremiah 31:34, where the Lord declares, “I will forgive their iniquity, and I will remember their sin no more.” One might see in this statement a reference to the cross, where the true forgiveness of sin was actually accomplished.[8] After all, the book of Hebrews tells us that the blood of goats and bulls could never take away sins (10:4), and Romans tells us that God had passed over former sins until he put forth his own Son as a propitiatory sacrifice (3:25). In this regard, OT sacrifices were merely “IOU’s” or “promissory notes” that had no inherent power to forgive. So if Jeremiah 31 is talking about forgiveness actually accomplished, one may argue that it is a messianic prophecy. However, I think it may help to distinguish between the subjective and objective conditions for forgiveness. On the subjective side, forgiveness requires repentance. On the objective side, forgiveness requires an atoning sacrifice. It seems to me that Jeremiah’s prophecy is concerned with the subjective side.[9] I don’t see in Jeremiah any hint that something was fundamentally wrong with the OT sacrificial system per se. Although in retrospect we as Christians can say that the cross achieved our forgiveness, it is doubtful that that’s what Jeremiah had in mind.[10]

[1] Kingdom through Covenant, 64f.

[2] Ibid., 72f, 691.

[3] Wellum says that this is “merely a human epistemological problem,” but that we should still do our best to baptize only when we see evidence of regeneration (Kingdom through Covenant, 693). But this turns baptism into nothing more than a mark of our best guess, which nullifies any real efficacy to it and any material connection to the covenant (a point which Wellum would probably not deny). In fact, by spiritualizing the church, it undermines any material reality to the covenant whatsoever, even calling into question our ability to call a particular community of professing believers a church. This has the unintended effect of creating a dualistic split, elevating the spiritual at the expense of the physical. Does this really fit the NT picture of the church?

[4] Believer’s Baptism, 3-5.

[5] In The Case for Covenantal Infant Baptism, ed. Gregg Strawbridge (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R, 2003).

[6] C. John Collins, “The New Covenant and Redemptive History” (unpublished essay, 2012), 16.

[7] At the same time, proponents of the Traditional Reformed view must still account for the subjective language used in Jeremiah 31 and the parallel restoration prophecies in Deuteronomy and Ezekiel. Taken together, these prophecies form a picture of a people with transformed hearts and an unmediated knowledge of God and of his law. Surely, such language goes well beyond the realities we experience even today in the Christian church. After all, we are still a mixed company of regenerate and unregenerate. And even the most sanctified ones among us still need to hear instruction in God’s Word. So how does the Traditional Reformed view deal with this interpretive difficulty? Richard Pratt appeals to the concept of inaugurated eschatology—the tension between the “already” and the “not yet.” Many of the New Covenant promises have already come to fulfillment, but many others still await Christ’s return. It will not be until the Eschaton that we finally see the complete merger of the visible church and the invisible church. Pratt, 168. See also Williams, 215-216.

[8] So Williams, 216-217.

[9] Williams acknowledges that the problem as Jeremiah saw it was not the Mosaic Covenant per se, but rather Israel’s failure to keep it. Ibid., 210.

[10] For both objections, a connection to the Christian era may still be established typologically, with the return from exile setting a pattern that finds a heightened fulfillment at Calvary and Pentecost. Such a reading would respect the integrity of the prophecies in their original OT context.

September 11, 2015

September 11, 2015

I left this on Facebook but figured I’d leave it here as well:

Thanks Kyle. I’m very happy to see Augustine enter the discussion. However, I have two concerns, and a comment:

1) You did not include 1689 Federalism in your survey, which is significantly different than Progressive Covenantalism. It is the confessional reformed baptist position, while PC is unconfessional. http://www.1689federalism.com I would encourage you to take it into consideration if you are looking to present various views.

2) You appear to be quite reliant upon Moon and Rayburn’s analysis of Augustine (I didn’t see any quotes from Augustine himself – though I recognize this was a very brief presentation). I haven’t finished Moon’s treatment yet, but he and Rayburn are both Federal Visionists who are trying to use Augustine to support their view of the covenant of grace. As it stands, your summary of Augustine is not at all in line with what I have read from Augustine. He does not categorize the Old and New Covenants as two aspects or ways of relating to one covenant. He is very clear that Old Covenant refers to the Mosaic Covenant itself. While he does believe that all OT saints who were saved were saved by their membership in the New Covenant, he very clearly says it is a distinct covenant, not a subjective way of relating to the Mosaic covenant. The promises and means of obtaining the promises are different, according to Augustine.

I would appreciate any quotes/references you can provide from Augustine.

“As then the law of works, which was written on the tables of stone, and its reward, the land of promise, which the house of the carnal Israel after their liberation from Egypt received, belonged to the old testament [covenant], so the law of faith, written on the heart, and its reward, the beatific vision which the house of the spiritual Israel, when delivered from the present world, shall perceive, belong to the new testament [covenant]… I beg of you, however, carefully to observe, as far as you can, what I am endeavouring to prove with so much effort. When the prophet promised a new covenant, not according to the covenant which had been formerly made with the people of Israel when liberated from Egypt, he said nothing about a change in the sacrifices or any sacred ordinances, although such change, too, was without doubt to follow, as we see in fact that it did follow, even as the same prophetic scripture testifies in many other passages; but he simply called attention to this difference, that God would impress His laws on the mind of those who belonged to this covenant, and would write them in their hearts, (Jer 31:32-33)… These pertain to the new testament [covenant], are the children of promise, and are regenerated by God the Father and a free mother. Of this kind were all the righteous men of old, and Moses himself, the minister of the old testament, the heir of the new,—because of the faith whereby we live, of one and the same they lived, believing the incarnation, passion, and resurrection of Christ as future, which we believe as already accomplished”

-Augustine (Treatise on the Spirit and the Letter, c. 41, 42; A Treatise Against Two Letters of the Pelagians, b.3 c. 11)

http://www.1689federalism.com/augustine-proto-1689-federalist/

3) Augustine’s view was picked up by Lutherans and by Owen as well (who says he sided with the Lutherans, over against the reformed, on this point):

“And so it finally came to the most perfect promise of all, that of the new testament, in which, with plain words, life and salvation are freely promised, and actually granted to those who believe the promise. And he distinguishes this testament from the old one by a particular mark when he calls it the “new testament” [Luke 22:20; I Cor. 11:25]. For the old testament given through Moses was not a promise of forgiveness of sins or of eternal things, but of temporal things, namely, of the land of Canaan, by which no man was renewed in spirit to lay hold on the heavenly inheritance.”

-Luther (The Babylonian Captivity of the Church)

“Having shown in what sense the covenant of grace is called “the new covenant,” in this distinction and opposition to the old covenant, so I shall propose several things which relate to the nature of the first covenant, which manifest it to have been a distinct covenant, and not a mere administration of the covenant of grace…

This covenant [Sinai] thus made, with these ends and promises, did never save nor condemn any man eternally. All that lived under the administration of it did attain eternal life, or perished for ever, but not by virtue of this covenant as formally such. It did, indeed, revive the commanding power and sanction of the first covenant of works; and therein, as the apostle speaks, was “the ministry of condemnation,” 2 Cor. iii. 9; for “by the deeds of the law can no flesh be justified.” And on the other hand, it directed also unto the promise, which was the instrument of life and salvation unto all that did believe. But as unto what it had of its own, it was confined unto things temporal. Believers were saved under it, but not by virtue of it. Sinners perished eternally under it, but by the curse of the original law of works…

The greatest and utmost mercies that God ever intended to communicate unto the church, and to bless it withal, were enclosed in the new covenant. Nor doth the efficacy of the mediation of Christ extend itself beyond the verge and compass thereof; for he is only the mediator and surety of this covenant.”

-Owen (Commentary, Hebrews 8:6)

My own background and conviction is baptistic. I’ll make a few observations for your reflection. I think the new covenant is by definition a covenant for believers. Of course this doesn’t mean that all who claim to be believers are in it. It does, however, mean that only those who are understood to be believers should be administered its sacraments. Unlike previous covenants this is a covenant for those events born ‘not of blood’ (Jn 1).

Jeremiah foresees the new covenant promise reaching to succeeding generations of Israel. Peter extends this to ‘those far off, as many as the Lord will call’ (Acts 2). I don’t think Jeremiah reveals how the children will become covenant members, however, the Acts text defines the covenant members and how they become so by the phrase ‘as many as the Lord will call’. Incidentally does this text not tie baptism firmly with the new Covenant. It mentions the promise, the forgiveness of sins, and the gift of the Spirit within the context of baptism.

It is difficult to judge the spiritual status of OT saints. Certainly all had circumcised hearts. All were regenerate. In some sense the Spirit must have operated within them. Hebrews describes them as ‘just men’ (Hebs 12). Abraham was justified by faith. Yet there is a qualitative difference between believers before Pentecost and believers after Pentecost. When Christ said he would build his church he was thinking about his disciples and beyond. None in the old era was greater than John the Baptist but he that was least in the kingdom was greater than he. The age of the kingdom is the age of the new covenant the age of the church. It is the age of union with Christ. OT saints were awaiting the ‘perfection’ that we have already in a sense entered into.

There is much you say that I can agree with. I am not convinced you make a good case for children being new covenant members. This seems to miss the heart of the new covenant being one of forgiveness and the indwelling Spirit.

Is not the return from exile better located at Christ’s coming? (Matt 1).

Thank you for another careful reflection that has instructed me.